Biofuels and the Ecological Transition in Europe

Sustainability, raw materials and competitiveness: the European dilemma

Published by Luigi Bidoia. .

Biofuels Bio-Based Chemicals Price DriversThe two main areas in which bio-based chemistry has developed are chemical intermediates[1] and biofuels. This article focuses on the latter, with a specific emphasis on biodiesel, analysing its role in the European context of the ecological transition, at the intersection of environmental sustainability, security of raw material supply, and industrial competitiveness.

The biofuels sector encompasses a wide range of products. However, only two of them exhibit a global production scale on the order of 100 million tonnes: ethanol and biodiesel. The former is used as an additive or partial substitute for gasoline[2], while the latter is employed as an additive or substitute for diesel fuel.

Two different biodiesels

The term biodiesel actually refers to two products that are chemically very different from each other. They are obtained through distinct industrial processes, but share common feedstocks, namely vegetable oils and animal fats, either of virgin origin (such as rapeseed, palm, and soybean oils) or derived from waste streams, such as UCOs (Used Cooking Oils).

-

FAME biodiesel (Fatty Acid Methyl Esters):

it consists of methyl esters of fatty acids. Its physico-chemical properties differ from those of fossil diesel and, in general, its use leads to lower emissions of particulate matter, CO, and hydrocarbons at the exhaust, albeit with a possible increase in NOx emissions. In the European Union, it is typically blended with diesel fuel, with a maximum content generally ranging between 7% and 10% (B7 and B10). More recently, a B100 biodiesel has been introduced to the market for heavy-duty vehicles specifically approved for its use. -

HVO diesel (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil):

it is a paraffinic hydrocarbon obtained through hydrotreatment. It has properties very similar to those of fossil diesel, while allowing for a significant reduction in particulate matter emissions at the exhaust and in life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions. It can be used at 100% (drop-in, i.e. fully interchangeable with conventional diesel) without blending limits and is particularly well suited for modern engines, such as those compliant with the Euro 6 standard.

FAME biodiesel was introduced to the global market several decades ago, whereas HVO diesel is a more recent development. The latter, however, is rapidly gaining market share. According to data from the European Biodiesel Board (EBB), in 2019 the breakdown of the European Union market between FAME and HVO was 83% and 17%, respectively. By 2025, the share of HVO had risen to 21% and is expected to reach 23% by 2027. We are therefore witnessing a phase of progressive substitution between the two types of biofuel.

FAME biodiesel: global trade and international prices

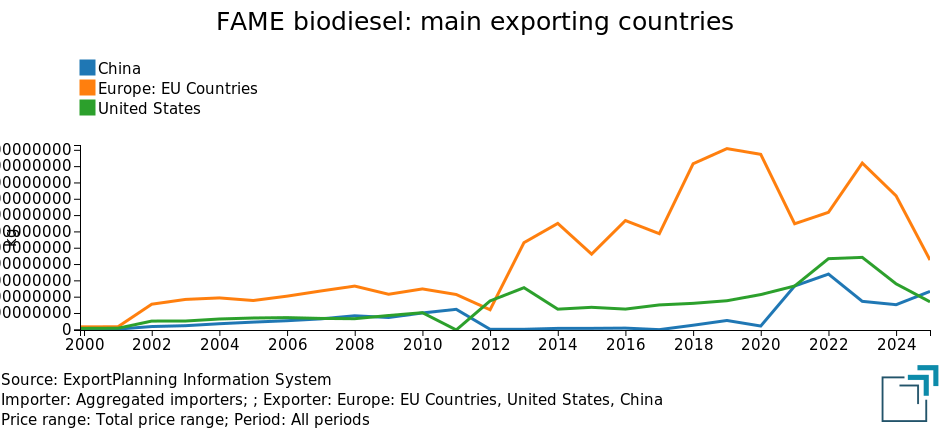

Focusing specifically on FAME biodiesel, the European Union holds a leading position at the global level, followed by the United States. In recent years, however, these positions have become less firmly established due to the increasing competitive pressure exerted by China, as illustrated by the chart shown here. The chart depicts the shares of global FAME biodiesel trade (excluding intra-EU flows) attributable to the aggregate of EU countries, the United States, and China.

FAME biodiesel: main exporting countries

The development of global demand for FAME biodiesel experienced strong growth during the second decade of this century, largely supported by the export capacity of European companies. Over the past five years, however, the position of the European Union has progressively weakened, first in favour of the United States and subsequently of China. China, in particular, appears to have been able in 2025 to offset the effects of increasing competition from HVO in the global biodiesel market, emerging as the only country to increase its exports of FAME biodiesel.

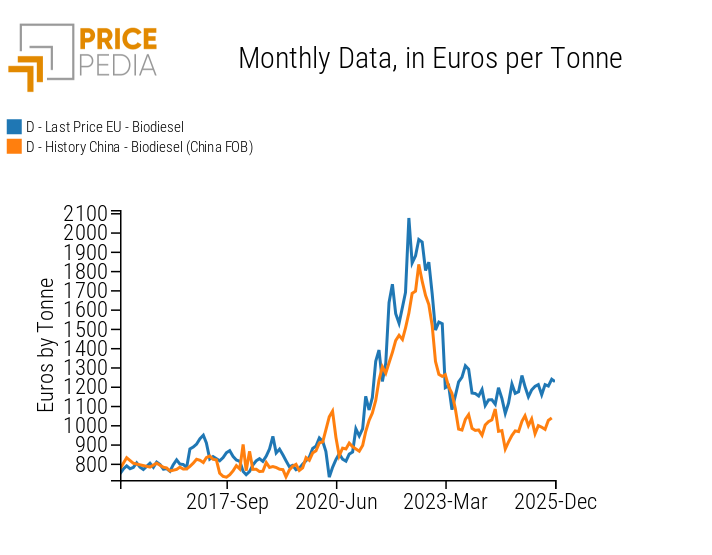

China’s greater competitiveness in global FAME biodiesel trade is also evident from the comparison between Chinese FOB export prices and the customs prices of intra-EU trade, as shown in the chart below.

FAME biodiesel: Comparison between EU prices and Chinese FOB prices

FAME biodiesel prices in the European Union and China remained broadly aligned until mid-2023. Thereafter, a significant price differential emerged, with EU prices averaging around 20% higher than Chinese prices.

In response to possible dumping practices by Chinese companies on the EU market, the European Commission launched, at the end of 2023 and at the initiative of the European Biodiesel Board (EBB), an anti-dumping investigation into Chinese FAME biodiesel exports. This procedure led, in February 2025, to the adoption of a definitive measure introducing anti-dumping duties with rates ranging between 10% and 35.6% (see the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/261 of 10 February 2025 imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty on imports of biodiesel originating in the People’s Republic of China).

Conclusions

Together with bio-based intermediates, biofuels can play a strategic role in the ecological transition of the European energy system. In order to reduce competition with the food industry on agricultural raw material markets, the European Commission has progressively introduced a distinction between conventional biofuels (first-generation biofuels derived from virgin vegetable oils) and advanced biofuels, produced from waste-based biomass such as used cooking oils (UCO, Used Cooking Oil).

This policy orientation is reflected in the sustainability targets and incentive mechanisms set out in European energy legislation, in particular in the RED II Directive (Renewable Energy Directive), which favours advanced biofuels over conventional ones, thereby shaping industrial strategies and investment decisions across the sector.

The outcome is a transition pathway that is more consistent from an environmental perspective for the European economy, but one that is also accompanied by increasing regulation of the biofuels industry. This framework may translate into a loss of competitiveness and into price levels that are, on average, higher than those prevailing in extra-EU markets. The biofuels sector therefore clearly illustrates the difficult balance between the degree of environmental ambition embedded in transition pathways and their associated economic and industrial costs.

[1] For an analysis of bio-based chemical intermediates, see the article Bio-based chemistry: a strategic innovation for the ecological transition

[2] For an in-depth discussion of the global ethanol market and its international price dynamics, see the article The United States at the centre of the global ethanol market