From Iodine to Its Salts: A Market Dominated by a Single Element

High prices and a significant mass contribution make iodine the key cost driver of its salts

Published by Luigi Bidoia. .

Inorganic Chemicals Cost pass-throughPersistent Tensions in the Global Iodine Market

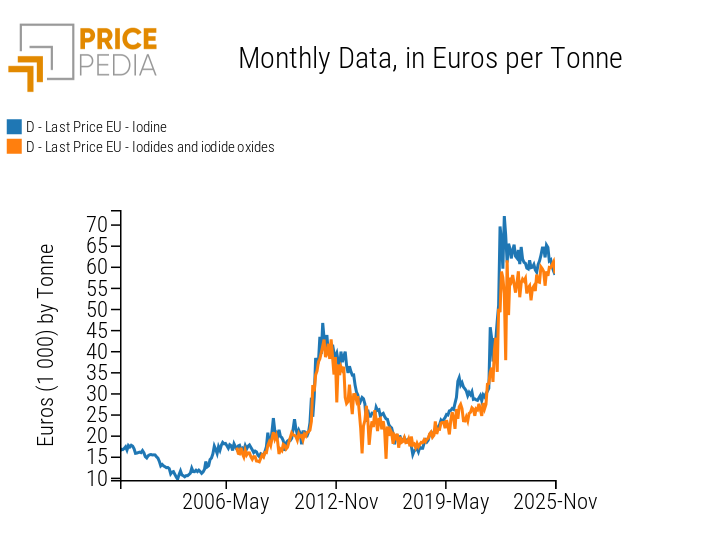

In recent years, iodine has experienced a marked increase in scarcity across international markets. For 3 years now, a kilogram of iodine has been traded at a price above 60 euros/kg, placing it among the most expensive basic chemicals. In the latest commodity price cycle, iodine has followed an independent trajectory: while it posted a decline in 2021, it continued to rise sharply in both 2022 and 2023. As described in Iodine: the effects of a high concentration of world supply, the main drivers behind this trend lie in the strong concentration of production in a few countries and in the difficulty of expanding supply in line with sustained demand growth.

Global Iodine Supply

There are essentially two industrial processes for producing iodine, and both face structural limitations in expanding supply. The first involves extracting iodine from caliche, a rare mineral found in significant concentrations only in certain mining areas of Chile. The second process is linked to hydrocarbon extraction, which sometimes yields brines from which iodine can be recovered. However, production levels of iodine derived as a by-product of hydrocarbon extraction are not driven by iodine prices, given its limited output and negligible contribution to overall revenues compared with hydrocarbons.

As a result, global iodine production is inherently constrained. In Chile, it is limited by the challenge of identifying new caliche deposits or intensifying the extraction of known ones. In other producing countries, it depends on decisions regarding hydrocarbon extraction. Overall, the global supply of iodine is poorly responsive to price changes, shifting the burden of market rebalancing primarily onto variations in demand.

Global Growth in Iodine Demand

Iodine is an essential element both for biological systems and for a wide range of industrial processes. Its unique physicochemical properties make it indispensable across sectors ranging from pharmaceuticals and healthcare to electronics, chemical synthesis, nuclear energy, and advanced batteries such as aluminum–iodine and lithium–iodine technologies.

The largest end-use segment for iodine worldwide is human and animal health, accounting for more than half of global demand. Its increasing use in human nutrition is supported by WHO-led salt iodization programs. In intensive livestock systems, iodine is added to feed to ensure animal health and productivity.

In the medical field, iodine is indispensable in the formulation of contrast media used for medical imaging. Iodinated contrast agents are widely applied in X-ray procedures, CT scans, and angiography, enabling clearer visualization of blood vessels, organs, and tumors. This demand continues to grow, driven by population aging and the expansion of high-intensity diagnostic systems.

Electronics and optics also represent a growing area of iodine consumption. Iodine-based compounds are used in the production of liquid crystal display (LCD) polarizing films, where they align polymer layers to control light transmission. This application is closely linked to consumer electronics, automotive displays, and photovoltaic panels.

Finally, iodine is used in water treatment—complementing chlorine-based systems—, in numerous chemical applications as a catalyst, reagent, and stabilizer, and to enhance the performance of advanced battery technologies.

Limited Substitutability

The unique properties of iodine make it difficult to replace in many essential applications. Where substitution is technically possible, it typically involves trade-offs in performance, cost, environmental impact, or regulatory compliance. As a result, the technical substitution potential for iodine is limited.

Economic substitutability is also generally low, as the cost of iodine per unit of final output is often modest relative to the overall value of the process. In many cases, despite the high price per unit of iodine, its contribution to total production costs remains limited, making substitution economically unattractive.

The low substitutability of iodine—both technical and economic—translates into very low demand elasticity with respect to price changes. Even substantial price increases are insufficient to significantly reduce consumption, which continues to grow under the influence of the drivers described in the previous sections.

The Effects on Iodine Prices and Derived Salts

The limited elasticity of both supply and demand with respect to price changes makes the global iodine market highly sensitive to any external shock capable of altering production or consumption levels.

As noted earlier, the market tensions of recent years led to a doubling of iodine prices during 2022–2023, followed by a period of stabilization over the subsequent two years. A key feature of the iodine industry and its derivatives is that increases in iodine prices tend to be passed through almost entirely to the prices of iodides[1], its main downstream products.

In the chart below, the comparison between iodine prices and the average price of iodides clearly shows how increases in the price of iodine have translated into nearly equivalent increases in the average price of iodides.

Comparison between prices of iodine and iodides

The near-full transmission of iodine price increases—per kilogram or per ton—into equivalent rises in iodide prices depends on two main factors: the high atomic weight of iodine and its much higher unit price compared with the other elements involved.

Iodine has an atomic weight of 126.9, significantly higher than that of alkali metals such as potassium (39.1) and sodium (23.0), or metals like copper (63.5). As a result, the production of major iodides requires relatively large weight fractions of iodine. For example, the iodine content needed to produce potassium iodide (KI), sodium iodide (NaI), and copper iodide (CuI) corresponds to 76.4%, 84.6%, and 66.6% of their respective molecular weights.

Moreover, given that the price of iodine is far higher than that of potassium, sodium, or copper, the share of iodine in the total raw material cost exceeds 99% for potassium iodide and sodium iodide, and is around 94% for copper iodide.

With such high cost shares, it is natural that the price per ton of iodides closely mirrors the price of iodine.

Conclusions

The high atomic weight of iodine and its much higher price per ton compared with the atomic weight and price of the metals with which it combines to form iodides result in a very large cost contribution of iodine to the total raw material cost of iodide production. This contribution generally exceeds 90% and rises above 99% for the two most important iodides: potassium iodide and sodium iodide. Under these conditions, iodide prices tend to remain very close to iodine prices.

The recent tensions in the global iodine market — which in 2023 led to average prices roughly double those observed at the beginning of the decade — have been passed through almost entirely to iodide prices. From a market and pricing perspective, iodine and iodides can therefore be considered as a single commodity category. Given the low price elasticity of both demand and, especially, supply, the prices of iodine and iodides remain exposed to significant future fluctuations, with upward risks greater than downward risks.

[1] Iodides are the salts formed when iodine combines with metals, particularly alkali metals. The most important examples are potassium iodide and sodium iodide. Overall, the production of iodides represents a relatively small share of total iodine consumption.